“Commanding Everything, Winning Nothing" ...

The Strategic Limits, and Hubris, of 'Full-Spectrum Dominance'.

"Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals."

—President Dwight D. Eisenhower

I. Introduction

In 2000, the U.S. military unveiled a bold ambition: Full-Spectrum Dominance (FSD). It promised not just battlefield superiority but decisive control across land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace, along with the information domain.

For a post-Cold War ‘superpower’ basking in unipolar preeminence, the logic seemed airtight.

Yet, as the 21st century progressed—riven by insurgencies, cyber intrusions, disinformation campaigns, and the erosion of U.S. moral capital—the limits, contradictions, and internal paradoxes of the FSD doctrine came sharply into view.

This essay provides a critical examination of Full-Spectrum Dominance—its origins, doctrinal transformations, and strategic implications—and interrogates the friction between the aspiration for dominance and the moral-political character of the American democratic experiment.

Finally, it situates this evolution within the theory of Compound Security Competition (CsC), advancing a polycentric framework better suited to an age of complexity and contestation.

II. Pedigree and Emergence: Full-Spectrum Dominance in Strategic Context

The concept of “Full-Spectrum Dominance” (FSD) crystallized during a period of unparalleled U.S. geostrategic primacy—a post-Cold War moment marked by triumphalism, where American exceptionalism and technological supremacy appeared to promise global order on U.S. terms.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 created a vacuum in global polarity, ushering in what Charles Krauthammer termed the “unipolar moment.”

With the U.S. at the uncontested apex of international power, successive presidential administrations embraced the notion that American military supremacy could not only deter great power conflict but shape the global environment.

Under President George H. W. Bush, the decisive victory in the 1991 Gulf War provided the first full demonstration of emerging precision-strike capabilities, joint-force synchronization, and real-time battle management through technologies like JSTARS and GPS-guided munitions.

This war served as a proof-of-concept for the so-called “Revolution in Military Affairs” (RMA)—a techno-strategic thesis asserting that information dominance, sensor fusion, and precision effects could deliver battlefield omniscience and operational superiority.

The Clinton administration institutionalized this vision in doctrinal terms. In 1996, Joint Vision 2010, championed by Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. John Shalikashvili, established a conceptual framework centered on four tenets:

Dominant Maneuver

Precision Engagement

Focused Logistics

Full-Dimensional Protection

These pillars were designed to support a broader strategic objective: achieving dominance across all phases of conflict and in all domains of warfare.

By 2000, under President Bill Clinton’s second term, this vision was sharpened and expanded in Joint Vision 2020, directed by Gen. Henry Shelton. Here, Full-Spectrum Dominance was formally articulated as:

"The ability to defeat any adversary and control any situation across the full range of military operations."

This was not merely a tactical or operational ambition—it was a strategic worldview, grounded in the assumption that American technological superiority, if fully integrated across services and domains, could enable persistent and decisive control of the battlespace.

This vision was undergirded by three principal conceptual and doctrinal pillars:

The Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA): Asserted that information-age technologies—particularly intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) platforms, precision-guided munitions (PGMs), and command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) systems—could radically reshape the character of warfare.

The AirLand Battle Doctrine (1982–1990s): Originating in the Reagan era, this doctrine emphasized deep operations, synchronization across services, and maneuver warfare—a foundational predecessor to joint operational thinking.

Network-Centric Warfare (NCW): Popularized in the late 1990s and early 2000s by theorists like Vice Admiral Arthur Cebrowski, NCW posited that information superiority and networked forces could create “shared battlespace awareness” and accelerate decision cycles to outpace any adversary.

The resulting worldview was clear and self-assured: technological mastery would yield strategic supremacy.

Yet, as Clausewitz cautioned, war is never simply a technical contest—it is an extension of politics by other means, driven by human will, uncertainty, and chance.

The flaw of FSD lay not in its ambition, but in its conflation of capability with control, and of dominance with durable strategic outcomes.

III. Implementation and Dissonance: Iraq, Afghanistan, and Strategic Failure

While U.S. forces rapidly decapitated regimes in Iraq (2003) and Afghanistan (2001), strategic success remained elusive.

The adversaries—insurgents, ideologues, corrupt political systems—were not amenable to technological solutions alone.

Key contradictions emerged:

FSD confused operational dominance with strategic victory.

It undervalued human terrain, legitimacy, and post-conflict governance.

It bred a “can-do” hubris that obscured critical limitations.

In many ways, FSD was a doctrine of control born in an age increasingly characterized by uncontrollability.

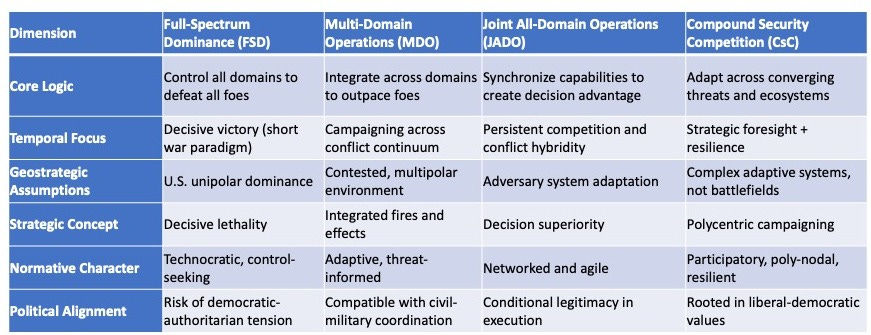

IV. Doctrinal Adaptation: From FSD to MDO and JADO

By the mid-2010s, the Department of Defense began revising its approach, acknowledging adversaries' capacity to challenge U.S. power in novel ways—especially in the gray zone and the information environment.

V. The Normative Tension: Can a Republic Dominate All? Should It?

The term “dominance” itself is at odds with foundational principles of liberal democracy:

Consent vs. Control: A republic draws legitimacy from consent, not from its capacity to dominate.

Civilian Supremacy: FSD’s technocratic allure risks marginalizing political judgment and the moral underpinnings of force.

Transparency and Restraint: In liberal systems, force must be constrained and scrutinized—dominance resists scrutiny.

These tensions become acute in gray zones and information operations where the means of dominance—surveillance, cognitive warfare, strategic deception—can easily transgress democratic norms.

VI. A Compound Security Alternative: From Control to Resilience

The theory of Compound Security Competition (CsC) offers a more strategically and ethically aligned framework for the 21st century:

CsC recognizes that threats today are convergent, transregional, and multi-dimensional (e.g., cyber, climate, health, extremism).

It emphasizes 3D+C: Diplomacy, Defense, Development + Commercial levers, applied in polycentric coalitions.

It accepts that uncertainty, not dominance, defines the current security epoch.

Instead of striving for command and control, CsC prioritizes strategic agility, coalition resilience, and influence-by-engagement.

VII. Conclusion: Beyond Dominance, Toward Strategic Statecraft

Full-Spectrum Dominance was a product of its time—a confident blueprint for a unipolar power in a seemingly unipolar world.

But its limitations—both operational and normative—have since been laid bare.

Strategic success in the compound era does not lie in controlling every domain but in mastering the art of adaptive, integrative statecraft.

The United States, as a liberal democratic republic, must resist doctrines that undermine the very values it seeks to defend.

In the age of compound security, the strategic imperative is not dominance—it is durability, legitimacy, and strategic influence, secured through compound, integrative, and value-consistent engagement.